Phucking with phishers

You talkin’ to me?

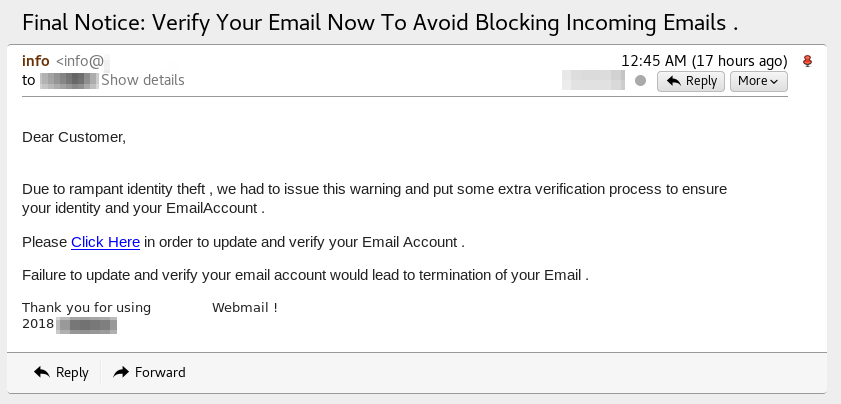

So there I was, minding my own business, checking my emails, when suddenly, a wild phishing attempt appears!

Yawn. Routine occurrence, right? The only notable aspect to this attempt was that it seemed to be specifically targeting users of the email platform that I use. I don’t use one of the big platforms like gmail or hotmail, so this was a little more notable than the norm.

Note: While I’m redacting the name of my mail provider, I hold no illusion about its discoverability. If you are intent enough you can figure out who I use. Don’t dox me, bro.

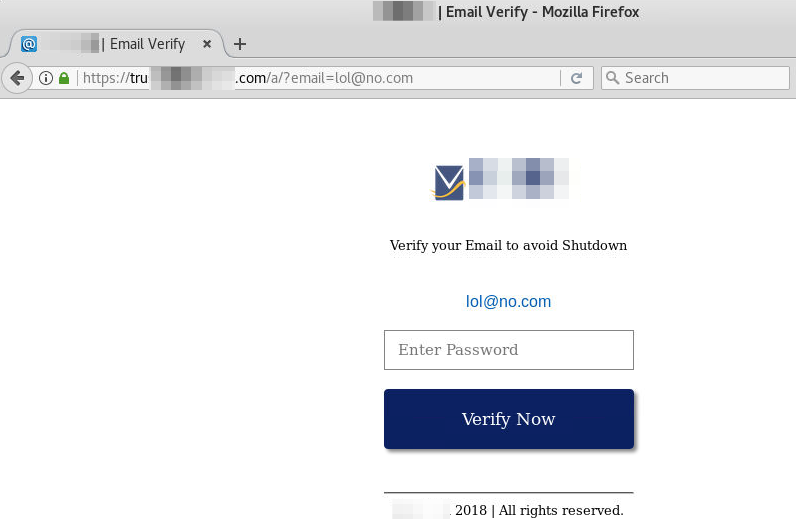

All right, so I’m curious. I hop into a temporary VPS on sadd.io and load up the page, modifying the URL not to include my actual email address (which the phishing link did. Sneaky phishers.)

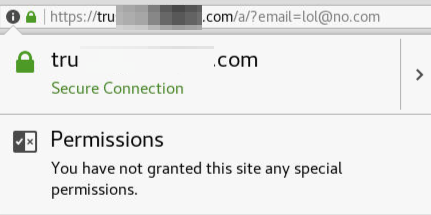

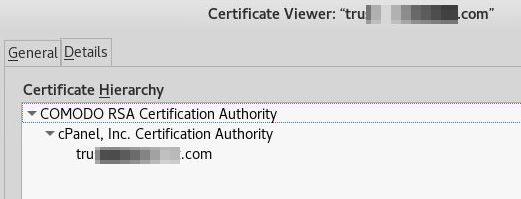

Well, that’s a bit phishy. Quick! Pop quiz! What do we do? My security awareness training told me how to spot a phishing site! I just check to see if the green padlock is th.. oh, hmm…

Btw, Comodo, you might want to have a talk with cPanel…

Ok, well, if I fill out the form it just redirects me to my authentic webmail provider, so this is obviously a simple credential scraping site. Time to report to all the phishing reputation sites, and in the time I write this post the site has gone from zero hits on Virustotal to half a dozen, so this will be short lived.

Hmmm…

Still… It makes one think, doesn’t it? The phisher’s goal is to get valid credentials. They want to get the passwords for email addresses they were able to enumerate through whatever means, and use them for nefarious purposes. The page is basic, and it likely just results in a small database (or even a flat file) made up of email address + password pairs, one for each submission to the site.

What if, hypothetically, an automated process started submitting a large number of bogus submissions to the form, resulting in the criminal’s database of accounts and passwords being full of useless garbage? That would be at least a little annoying, right? They would have to parse through the results to see if they got any valid credentials before they could attack them. If the number of bogus entries was large enough and convincing enough, finding the real ones to attack would be like picking out needles from a hay stack, or at least like sorting out all the red cards from a shuffled deck. Would it ruin their chances or their day? Probably not… but it might just annoy them a little.

Good enough.

The problem!

So, as a purely academic thought exercise, how would we go about creating such a hay stack/deck of cards? Let’s break the idea down into pieces:

- We need to submit the form repeatedly. Like a whole bunch of times. Definitely more than five.

- We need to generate submissions that are unique, in case the system clobbers repeat entries.

Well, for requirement 1, we will need to go with some sort of scripting or programming. Since we’re talking about submitting HTTP(S) requests, the easiest approach will be a Python script with the Requests library imported.

For requirement 2, we could use a large list of useless information, such as the 6-digit numerical incrementing list over at the Seclists github repository.

What might such a script look like?

The answer (version 1)

#!/usr/bin/python3

# phishingisbad.py

import requests

# Change the UA from the default Requests/Python UA

headers = {

'User-Agent': 'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko',

}

# Open our list of digits

with open('6-digits-000000-999999.txt') as input_file:

# Loop through the document, and for each line...

for i, line in enumerate(input_file):

# Submit a POST request to the phishing site with an incrementing value for the email and pass. Disregard the redirect that follows.

r = requests.post('http://tru[REDACTED].com/a/post.php', data = {'email':'git@re.kt' + str(i),'pass':line}, allow_redirects=False, headers=headers)

# Print output to the console to confirm the server reseponse (optional)

print(r)

[ Edited to add: Some readers asked how I determined what to put in the “data” portion of the code above. That came from reviewing the source of the website. It was a simple form with two parameters named email and pass:

...

<input name="email" type="hidden"...>

...

<input name="pass" type="password"...>

...

I just used the requests format for submitting a form to include those two parameters. ]

So, if we were to (hypothetically) run this script pointed at the phishing page, it would submit just short of a million worthless entries that look like the following:

email:git@re.kt0;pass:000000

email:git@re.kt1;pass:000001

email:git@re.kt2;pass:000002

...

email:git@re.kt999997;pass:999997

email:git@re.kt999998;pass:999998

email:git@re.kt999999;pass:999999

It’s more complex

But of course, there are some problems, here. It would be pretty trivial to just filter out the noise, since all the passwords are strictly numerical, and the emails simply increment.

Better would be to randomly generate values for the email and password, so that each submitted entry is unique (enough) that they aren’t easy to filter out. If you’ve done much grepping and cutting in Linux, you will know that one of the simplest annoyances in a data set can be fields that aren’t of a predictable length, so we will want the length of each to vary, too.

Also, since by default the Requests library uses a known User-Agent string, we will want to obscure our requests a bit by changing that up.

New requirements

- We need to generate unpredictable* email values of variable length that are in a valid format.

- We need to generate unpredictable* password values of variable length.

- We need to randomize the User-Agent string on each request.

Taking them out of order, the password line will be easiest. We just need to generate a string of numbers and letters of varying length:

pwd = ''.join([random.choice(string.ascii_letters + string.digits) for n in xrange(random.randrange(6,32))])

I went with 6-32 since that seems like a realistic range for passwords to fall in.

Next, to create realistic but valid email values, we will need some arrays:

- One containing a list of TLDs

- One containing a list of mail provider domains

Then we can randomize a string followed by “@” and a randomly-chosen domain, followed by “.” and a randomly-chosen TLD.

tlds = [

'com',

'net',

'org',

'co.uk',

'de',

'in',

'il',

'ca',

'edu'

]

domains = [

'amazon',

'hotmail',

'gmail',

'microsoft',

'live',

'protonmail',

'yahoo',

'aol',

'msn',

'wanadoo',

'comcast'

]

eml = ''.join([random.choice(string.ascii_letters + string.digits) for n in xrange(random.randrange(3,10))]) + '@' + domains[random.randrange(0,10)] + '.' + tlds[random.randrange(0,8)]

I went with usernames of 3-10 characters as again, that seems like a realistic length.

Troubleshooting

The third requirement ended up causing me the most trouble, because I didn’t understand the format of the object that is required for the “headers” parameter in the Request library. Rather than it being a string, the headers parameter is a JSON object that requires a specific format. This makes it a little more complex than selecting a random value from an array:

headers = [

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/70.0.3538.102 Safari/537.36',

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/70.0.3538.110 Safari/537.36',

#... and 83 more

]

hdr = {

'User-Agent': "'" + headers[random.randrange(0,84)] + "'",

}

Last, we need to combine all these pieces, and create a request that will submit the form a few thousand times.

What do we end up with?

#!/usr/bin/python3

# phishingisbadv2

import random

import requests

import string

# Array of 85 most common User-Agent strings

headers = [

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/70.0.3538.102 Safari/537.36',

'Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/70.0.3538.110 Safari/537.36',

# ... and 83 more...

]

# A hand full of TLDs

tlds = [

'com',

'net',

'org',

'co.uk',

'de',

'in',

'il',

'ca',

'edu'

]

# A hand full of mail provider domains

domains = [

'amazon',

'hotmail',

'gmail',

'microsoft',

'live',

'protonmail',

'yahoo',

'aol',

'msn',

'wanadoo',

'comcast'

]

# Loop a million times

for i in list(range(1000000)):

# Randomly select a header value

hdr = {

'User-Agent': "'" + headers[random.randrange(0,84)] + "'",

}

# Generate a random string@domain.tld combination

eml = ''.join([random.choice(string.ascii_letters + string.digits) for n in xrange(random.randrange(3,10))]) + '@' + domains[random.randrange(0,10)] + '.' + tlds[random.randrange(0,8)]

# Generate a random password value

pwd = ''.join([random.choice(string.ascii_letters + string.digits) for n in xrange(random.randrange(6,32))])

# Create and submit the request

r = requests.post('https://tru[REDACTED].com/a/post.php', data = {'email':eml,'pass':pwd}, allow_redirects=False, headers=hdr)

# Output the combination and result HTTP code (optional)

print("Submission count: " + str(i) + " - " + eml + " / " + pwd + " - " + str(r))

I’ve placed a copy of this code here for reference.

The output that would result from this setup is way more annoying to try and filter out, hopefully creating our desired hay stack:

email:MUayh@aol.il;pass:kItXDLsIwkYj

email:NexvUnFP@gmail.in;pass:Q3PeU6fD

email:rN21v@hotmail.in;pass:AVd14Q4AsA1dL

email:ft0fjv6@msn.net;pass:GWZ332Gq88

Closing thoughts

There are some definite shortcomings with the code, such as all the static references that could be made more dynamic and flexible, and the lack of any input variables or interaction. Still, it would (hypothetically) serve its purpose of wasting the time of phishers.

Another gap in the code above is that it goes directly to the form and submits it. A more robust approach would be to use the HTTP-Referer value that the preceding page would legitimately provide, in case the site author decided to put a check in place for that.

All in all, a fun thought exercise. I hope the example is useful.

* I know the code above is not “truly” random, and isn’t cryptographically sound, but I can have a reasonable degree of confidence that in this context it wouldn’t be very predictable, and even if it could be reverse-engineered, that would be far more work than it would be worth