Practical Password Guidance

Spoiler: There is no quick answer to this. I’m a details guy. This won’t be short.

What’s all this fuss about passwords?

I work as a security consultant, so one of my primary job functions is to provide recommendations to my clients. I typically identify some form of risk in their environment (of either a technical or operational nature), and then provide recommendations as to how to mitigate that risk, either partially or completely. Such recommendations can range from the very brief (“Install

Most of my recommendations are taken without much in the way of resistance, but one subject has always had a much higher proportion of questioning, disagreement, and downright arguing than any other: password strength recommendations. It used to be such an issue that I wrote up a two-page standard recommendation as the starting point of the ins and outs of password creation for my clients. That material is, of course, work proprietary, but there is so much to discuss on the subject I felt I should have something on here, too.

It’s no wonder that there are differences of opinion when it comes to passwords. There is no end to the advice online. Some of it good. Some of it really, really bad. Most of it in between, with some good elements and some bad. Some of it is compliance driven. Some of it is based on “best practices,” though nobody can even seem to agree on what that means. NIST, of course, has their updated guidance on everything from designing systems for password storage, to how users should be restricted from using weak passwords, to how often passwords should be reset. All of these sources have their strengths and weaknesses, but the root issue for users is the myriad conflicting, confusing, complex sources of information. This leaves users with questions and no clear answers.

- What source should a user trust for guidance?

- Which is more important? Length or complexity?

- What do weak passwords look like?

- What do strong passwords look like?

- How can I make better passwords?

- Do I really have to read 250 pages of guidance to know how to choose strong passwords?

These are complex questions, and there isn’t a single right answer to any of them, except perhaps that last one (the answer is no, you definitely don’t, and that’s not really what 800-63 is for.)

Instead of trying to prove answers to the first two questions above - which could justify a post each and still not be “solved” - I’m going dig into questions 3 through 5, provide examples, and describe my thought process as both a user and a white hat attacker. I will also go step-by-step through the Diceware model for generating passwords, give some opinions on the strengths and weaknesses of that approach, and provide an alternative method that I think has merit as a middle ground between strength and effort.

Important concepts

Before we get into the passwords themselves, there is some important background information that users might find helpful. It’s common advice that we shouldn’t use passwords that are “based on a dictionary word.” What gets lost in this advice is precisely what “dictionary” means.

For most of us, a dictionary word is self-explanatory. If you speak English, you might quite reasonably assume that a dictionary word is one of the roughly 300,000 words in the second edition of the Oxford English dictionary, but that isn’t the kind of dictionary an attacker will use to crack passwords. An attacker’s dictionary is far larger than the normal dictionary of a single language, and might consist of hundreds of millions of entries.

What do these entries look like? Well, to start, an attacker dictionary will include much - perhaps all - of the contents of traditional language dictionaries. It will probably include the entirety of one of the main authoritative dictionaries in the primary language that target passwords fall into (this is commonly English, but it’s a big world, out there). Next the dictionary may include the top most common words from other major world language dictionaries, since lots of English speakers think they are being clever when they use other languages for their passwords. So Achtung123 is just as likely to get cracked as Welcome123, and not simply because of brute force (though that, too). Conceptually we can replace “English” with any other base language and rotate, accordingly.

Next come phrases. While we traditionally think of dictionaries as only including single words, an attacker’s password cracking dictionary seeks to include common examples of various strings of words that might be used to make a password. Famous quotes, company slogans, lines from books, and lyrics from songs are all fair game for what ends up in a password cracking dictionary, so Snapintoaslimjim123 is also just as likely to get cracked as Welcome123. This time the brute force resistance is different between the two, but the dictionary-based vulnerability is just the same, if “snapintoaslimjim” is in the attacker’s dictionary (and it definitely is).

Also important to understand is that password cracking software doesn’t just take the dictionary as it is. It also applies rules to each entry. These rules are created based on common password usage trends, but more on that later.

So really, the principle for making better passwords is not to avoid those based on a traditional dictionary word, but rather to avoid those based on an attacker dictionary “word.” This is a higher bar to clear.

So what do we do now?

Use multifactor authentication and a password manager

I feel obliged to start with the best advice first. It really behooves all users to get into these habits. Most major sites support multifactor authentication of some form or other (receiving a text, or using an app that generates time-based codes, or in some cases receiving an Email containing a temporary code). It’s an annoyance, yes,. but it is worth it the vast majority of the time. Multifactor authentication can be enough to make an opportunistic attacker move on to easier prey, and that can keep you safe, online.

Similarly, while it takes some getting used to, relying on a password manager is far better than coming up with your own passwords. Humans are notoriously bad at estimating what is really random. (The images don’t load in that article, but can be found on archive.org). A password generator’s pseudo-randomness is far superior to that of humans, and once you get used to the workflow of storing your passwords inside one, it’s much easier than trying to remember dozens of passwords.

What do weak passwords look like?

All right. With the background out of the way, next I am going to provide some examples of weak passwords, and why they are weak. Most of these will be obvious, but a few may surprise you.

- Admin

- Password

- Spring2019!

- !March2019?

- Welcome1234!

…

These are pretty obvious to everyone. They are based on a single (traditional) dictionary word, they are commonly used, and some of them are even defaults on software and hardware devices. You might also note that while there are special characters in some of them, they are either at the beginning or the end of the password. This is bad because it’s common for other people to do it. The baddies know this, and have crafted their tools to compensate. Remember the rules I mentioned before? Some of the most common rules could be read as “append a special character,” or “prepend a special character.” Such a rule would take the input of “Welcome” and try:

- Welcome!

- Welcome@

- Welcome#

- Welcome%

… etc.

Other rules might be “append the numerals 19 and then two more numerals from 00 to 99.” This would result in:

- Welcome1900

- Welcome1901

… - Welcome1999

Another might be simply “append the numerals 1234,” giving us:

- Welcome1234

And rules can be combined, so we might also end up with:

- Welcome1901!

- Welcome1902!

… - Welcome1234!

… - Welcome1901@

- Welcome1902@

… - Welcome1234@

… etc.

There are tons of rule sets for “mangling” passwords in this way. Capitalize the first letter. Capitalize all the letters. Capitalize none of the letters. Append. Prepend. The list goes on.

How about another example of a bad password…

- W3lc0m31234!

But wait. Haven’t we been taught for years that replacing letters with numbers is a good way to make a password stronger? Yes, we have. Rewinding 10 years, that was probably still reasonably sound advice. The problem is, as I said, that the baddies know this technique, and there are rules for these common transformations. If you replace o with 0, or e with 3, or a with 4, or t with 7, you are wasting time and effort. Those old rules make it harder for you to type the password, but they don’t make it significantly harder for a computer to crack it.

Back to the bad examples:

- WhyMe?1984!

- [redacted]Sucks!

- AmazonPass123

- Michaelis13!

Some of these might look surprising, or made up, but, with the slight modification of redacting the name of the company that a person worked for, they are all real passwords that I have cracked in real engagements. They are, respectively:

- A secret cry for help

- A complaint about an apparently terrible employer

- Somebody’s Amazon password

- A factual detail about a person’s child.

They all follow the same basic premise of being based on a single (or a combination of a couple) traditional dictionary words, plus some numbers and symbols. The last one is doubly bad because it also is made up of common details that a ton of people might know about that user.

The last examples are some of my favorites:

- Subwayeatfresh!

- Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn1

The subway one is pretty obvious, in hindsight, but it stands out in my memory as when I learned that slogans were included in attacker dictionaries. As a famous company slogan, it ends up in the attacker’s dictionary, and yes, I’ve seen it on a live engagement. But come on. Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn1? There’s no way that will… wait, they did what?.

All right, then. Avoid common/famous lines from books, company slogans, speeches, etc.

What do strong passwords look like?

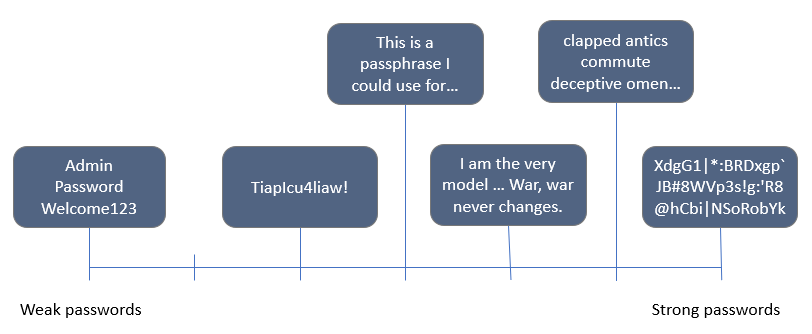

Here are some examples of passwords of increasing strength (note that #1 and #2 are swapped because #2 is derived from #1):

- This is a passphrase I could use for logging into a website (59 characters)

- Pros: This is super easy to remember and type, because it’s plain language. It naturally include changes of case and special characters (spaces). It’s also very unlikely to show up in a dictionary (or it was, until I posted this blog).

- Cons: This doesn’t do anything unique to transform (“mangle)”) the password. The only capital is at the start (a common pattern) and the only special symbol is a space between words. You also have to come up with every word yourself. Some sites do not allow passwords this long. Good, but could be better.

- TiapIcu4li2aw! (14 characters)

- This password is generated by taking the first character from each word in the passphrase above. Though it follows in sequence, I consider it all around worse than the passphrase above.

- Pros: It’s just as easy to remember (you memorize the phrase), and it has a little more complexity. It’s more likely to be acceptable to most sites. Bruce Schneier recommends this method.

- Cons: It’s more difficult to type. It’s far shorter, which renders it more likely to be brute-forced than the original passphrase. That said, it’s still pretty resistant to cracking or brute forcing.

- I am the very model of a modern major general. War, war never changes. (70 characters)

- This is a “middle ground” alternative to Diceware. I’ll explain its creation method later in this post.

- Pros: Long and very easy to remember and type. You only have to memorize two elements. Very resistant to brute force, very unlikely to be in a dictionary (until this post).

- Cons: Shares some of the same problems as the first passphrase above. It doesn’t really mangle the phrase at all, and it might simply be too long for some systems.

- clapped antics commute deceptive omen fragment (46 characters)

- This one looks a little odd at first. It’s a balance of random generation (through the use of dice, described below) and a published word list.

- Pros: Easy to type. Randomly determined from a list of thousands of words. You can usually form a mental image of the words to help remember it (or re-roll a word or two if the words just don’t work together at all).

- Cons: Not mangled at all, and the word list is public. It’s a good idea to do some mangling of your own if you use this method. You also have to get out dice and refer to a list.

- XdgG1|*:BRDxgp` (15 randomly generated characters)

- A password generated by a trusted password manager program. Keep in mind that once you get used to using a password manager, there is no real difference between using a 15 character password and a 100 character password, so might as well go longer:

- XdgG1|*:BRDxgp`JB#8WVp3s!g:’R8@hCbi|NSoRobYkiXLB|V (50 randomly generated characters)

- Pros: These passwords are the most resistant to cracking or guessing. Since they are randomly generated, brute forcing is really the only way to break such a password (though, like any password, it could still be intercepted). Passwords like this are generated by password managers, and once you have use of a password manager as part of your workflow, you don’t even have to think about memorizing such a password. Just copy and paste it.

- Cons: Basically impossible to memorize. A pain in the butt if you ever do have to type it manually. All but unusable for mobile devices (phones, tablets). Length again may be a limitation on some sites.

If I were to visually represent the relative strengths of these passwords, they would go nearly in the order above, with #1 and #2 swapped:

Note: The representation isn’t to any calculated scale, but rather evenly spaced on a ranking based on my qualitative view of each password based on its relative strength and its ease of use for the user.

General principles

There aren’t hard and fast rules to password creation, but these general principles are usually applicable:

- Length is generally more important than complexity.

- Longer with less complexity is usually better than shorter with more complexity (there are exceptions, don’t math me). That said, you should aim for both.

- Randomly generated phrases can be a good balance of memorable and long.

- See below re: Diceware for advice on creating some.

- Avoid personal information in your passwords (and security questions).

- Birthdays, relatives, cities, pets, anything on your Facebook or LinkedIn

- Do not reuse passwords across sites.

- If one site gets hacked, others could be accessed.

- Keep it secret, keep it safe!

- If you write it down, never leave it unattended.

- Don’t mangle the way everybody else does.

- Come up with your own secret mangling technique, such as “insert the letter R after every new word.” Something that other people aren’t doing.

- Use a password manager.

- It makes life easier and passwords more secure, but make sure you use a well-regarded one, and make sure you keep a backup somewhere safe!

- Be better than the minimum requirement

- If you only create a password that meets the minimum, you are the low bar by which others are measured.

Diceware?

I’ve mentioned Diceware a few times, now, so what’s that? Put briefly, it’s a method for creating passwords based on a couple of principles:

- Humans suck at randomness, computers are “ok” at it, but the real world is full of it.

- Lists of randomly-selected elements from a large enough pool are expensive to brute force.

Diceware basically takes the concept of brute force resistance in passwords and cranks it up a (few thousand) notches. With brute forcing, the passwords that can possibly be generated (the key space) are a combination of the length of the password and the number of possible characters that can be chosen.

I won’t get deep into the math in this post (I am by no means an expert), but there is plenty of good reading on the subject.

In short, traditional passwords are made up of typable characters (a-z, A-Z, 0-9, and special characters on the keyboard). Depending on your keyboard, this probably results in somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 characters to choose from. To brute force an 8-character password, we have to run all 8 characters through all their 100ish possibilities…

- aaaaaaaa

- baaaaaaa

- caaaaaaa

… - zzzzzzzz

- AAAAAAAA

- BAAAAAAA

… - Zaaaaaaa

- Zbaaaaaa

- Zcaaaaaa

… - ####ZZZZ

- ###$ZZZZ

- ###%ZZZZ

… etc.

With Diceware, you think of words as the characters from which to select, and that list is far larger than 100. The Diceware instructions will have you roll 5 dice (or one die five times) per word to choose from a list of 7,776 possibilities. If we create a diceware passphrase of 8 words, the number of possibilities is no longer 8 characters each having 100 possibilities, but rather 8 words each having 7,776 possibilities.

Even if an attacker knows that you used Diceware to make your password, simply running through all the permutations by brute force would be extremely costly, with today’s computing power.

Exercise time

So let’s make a Diceware password. Most nerds have at least one set of dice within easy reach, so grab yours, get a pencil and piece of paper, and let’s get started.

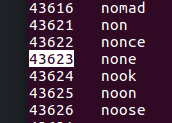

First, we need a word list. There are quite a few options, but for this example I will use the original Diceware wordlist.

Step 1 - Roll dice

The instructions say that we should roll 5 dice for each word, so we shake, rattle, and roll…

4 3 6 2 3

Step 2 - Find word

We look in the wordlist for the number represented by 43623 and find…

none.

So we write down ‘none’ and continue to…

Step 3 - Repeat

The current advice is for a minimum of six words, but I’ll go with eight to remain in line with the example from earlier:

- 63452 = warn

- 56135 = sunk

- 14133 = betty

- 42622 = mosaic

- 61631 = trig

- 34641 = jude

- 64232 = wince

Now we have a pass phrase of eight words: none warn sunk betty mosaic trig jude wince.

Step 4 - Memorize

The next step is to memorize the words. Depending on what you rolled, this might be easier or harder. You typically want to break the words up into a few mental “chunks” to make them easier to commit to memory. If you can form an image or a narrative of some kind with the words, that’s even better.

- “none warn sunk betty” could be remembered by picturing a famous Betty under the sea; she’s in danger, but nobody is warning her :(

- “mosaic trig” could be recalled by imagining one of those “math mosaic” educational tools.

- “jude wince” Another easy once, just imagine the familiar facial expression, and pair that up with a famous Jude (or a face that might be associated with the name, at least).

Now, it’s still a good idea to do some mangling of the diceware password once you create it. That way, even if somebody knows that you used diceware, and knows which list you used, they will still have a hard time of figuring out what kind of mangling you applied. After some modifications to the passphrase above, we might end up with something like:

- noneRwarnRsunkRbettyRmosaicRtrigRjudeRwince (replacing spaces with the letter R, because who does that?)

- noRne waRrn suRnk beRtty mosRaic trRig juRde wiRnce (inserting the letter R after every second character in each word, because who does that?)

- nonewarnsunkbetty mosaictrig judewince (grouping the words based on the “chunks” that were easy to remember)

- no0ne wa1rn su0nk be1tty mo1saic tr0ig ju9de wi5nce (inserting the birthdate “01011995” in the password. Not a great idea, but it gives you an example of how you could mangle the passphrase further)

All in all, not too bad, but that did take a few minutes. For those really important passwords that you need to remember (like the master password of a password manager), and that you can take time to plan in advance, this is probably a good technique.

An alternative to Diceware

Still, there might be times when I need to come up with a password, and it just isn’t convenient to follow the Diceware method:

- Traveling (and I forgot my lucky dice!)

- First day at a new job (and I forgot to prepare a new password in advance!)

- In a time-sensitive situation requiring a new password better than “Welcome123”

- Trying to convince somebody who just isn’t going to sit down with dice, pen and paper to come up with a new strong password

What to do? I’ve had success with an in-between method that borrows some rudimentary concepts from Diceware and simplifies them. Admittedly, this comes at the cost of weakening the resulting passphrases, but it can come in handy, and I think it has a benefit over just trying to come up with a series of random words on your own (remember, our brains aren’t good at random).

The basic concept is simple:

- Select a memorable phrase such as a quote, the lyric from a song, a line from a book, etc.

- Wait, didn’t you say doing that was bad? On its own, yes, but wait, there’s another step:

- Select a second, entirely unrelated phrase from some other source and combine the two.

Remember the example from earlier?

- I am the very model of a modern major general. War, war never changes.

^ Lyric from The Pirates of Penzance ^ Quote from the Fallout video game series.

Both of these parts, by themselves, show up in cracking dictionaries. But (prior to posting this blog), the combination of the two did not. There would be no reason for them to appear that way, because who would ever combine them?

There are some important principles that go with using this method:

- Do not select obvious sources. If everybody knows you love the musical “Hamilton,” avoid songs from it.

- Do not select two phrases from the same or related sources. Two quotes from different episodes of Naruto aren’t wise. Neither are two lines from different George R. R. Martin novels.

Why do I advocate this method? On its face, it seems like it’s just a weaker version of Diceware. Instead of it being a phrase made up of six or eight or ten “parts” there are only two. And we said before that humans are bad at being random. Both of these are true, but here are the key differences:

- We aren’t selecting from a known list. We have potentially any source of media to draw from (movies, TV shows, books, music, poems, speeches, etc.). The resulting choices can vary widely in their size and form. For one person, half the passphrase might be a quote. For another person it might be a mathematical formula. For another it might be a whole verse from a song.

- We aren’t trying to be random, we are deliberately selecting unrelated sources. It’s much easier to identify two elements that have no business being combined than it is to try and be “random.”

Examples

- There once was a man from Nantucket; y=mx+b (43 characters)

- There’s no place like home. You can’t serve this, it’s fucking RAW! (67 characters)

- A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away… I just met you, and this is crazy, but here’s my number, so call me, maybe? (121 characters)

These passphrases are easy to come up with, they are long (protecting from brute force), and they are very unlikely to be in an attacker’s dictionary.

It’s still a good idea to mangle them, though. Don’t forget!

You only need to remember a few passwords

Finally, I reiterate the guidance to use a password manager. It really does simplify life, and one of the ways it does so is minimizing the number of passwords we have to try and cram into our brains. There are only so many passwords most of us can remember before we start messing them up, or cutting corners and re-using them across sites, or making passwords that are technically different but really very similar. A password manager solves all these problems. Once you are in the habit of using a password manager, there is a pretty short list of passwords that you need to memorize:

- The master password to your password manager. (Obviously.)

- Your main email account password. (All your online accounts can be reset with this.)

- The password to your personal computer. (You will type this every day.)

- The password to your work computer. (Same with this.)

- The password to your phone/tablet. (You will enter this numerous times per day.)

- The password to your primary bank account. (Good to have in an emergency.)

Six is a much more manageable number of passwords. Some of us may have a couple more or a couple less to contend with, but my password manager currently has hundreds of entries that I wouldn’t have a hope of keeping track of without it. So I urge you to get a password manager. Try it out for a while, and then incorporate it into your regular workflow online.