Privacy, and the importance of metadata

Privacy is an important subject to me. I am a strong opponent of the argument that “if you haven’t done anything wrong, you have nothing to hide.” All it takes to prove such a silly notion wrong is to ask someone for their email password, or for them to hand over their phone so you might look through it, unrestricted. We all have plenty of embarrassing moments in life, in which we did nothing wrong, but we were glad that nobody was around to see. We all have private moments in which we do nothing bad or wrong, but which are certainly not the business of others. On this subject, and in the hope of helping others to understand why I care so much, I provide a good recent example on the importance of ‘metadata’ analysis. Often, in privacy parlance, metadata is referred to in the diminutive; that is, it is referred to as “only” metadata. Even a former president of the USA “clarified” the NSA’s monitoring program in this light.

The reality is that metadata is used to great effect to uniquely identify individuals in a number of different contexts (be that law enforcement’s constant efforts against terrorists, or Facebook’s tracking of our habits so they can best monetize advertisements to us, or a corrupt government’s efforts to suppress dissent).

To be clear, this is not a post about whether or not various organizations should be performing this analysis, or whether these activities are good or bad. Powers will analyze the data they have (and seek more), and the outcomes of such analysis can be good, bad, or neutral. Data and the techniques for analyzing it are tools, like any other. I think it is important for individuals to understand the implications of the collection of personal data in order to make informed opt-in or opt-out decisions about the services we use.

A new paper titled “You are your metadata,” (only a 10 page read, highly recommend) opens with this in their abstract of work they performed using machine learning to analyze public Twitter activity:

“… we are able to identify any user in a group of 10,000 with approximately 96.7% accuracy. Moreover, if we broaden the scope of our search and con-sider the 10 most likely candidates we increase the accuracy of the model to 99.22%. We also found that data obfuscation is hard and ineffective for this type of data: even after perturbing 60% of the training data, it is still possible to classify users with an accuracy higher than 95%.”

They go on to describe how the tool of data analysis can be leveraged:

“… this descriptive information can be actively analyzed and mined for a variety of purposes, often beyond the original design goals of the platforms. For example, information collected for targeted advertisement might be used to understand political and religious inclinations of a user.”

And, importantly:

“… even if an attacker only had access to anonymized datasets, by looking at the structure of the network someone may be able to re-identify users… We argue that the behavioral information contained in the metadata is just as informative.”

None of this should be surprising, but it isn’t something that most people think about. Online services do not come with large warnings that say You have little or no expectation of privacy while using this service. At best, a terms of use document or a privacy policy will use some obscure language that muddies the waters or even assures you that your data is safe and secure. Most of the time, it quite demonstrably isn’t.

Now, all this FUD isn’t to say that we shouldn’t use online services or social media. But as users, we have a responsibility to ourselves to understand the risk to our data, a duty to our friends and family to be cautious with what we share online that might impact them, and we deserve the right to be truthfully and reasonably informed about what companies are doing with our data. We also deserve control over that data.

One important distinction that Mark Zuckerberg made in his testimony before the United States Congress was between Data and Information. Unfortunately, it was a distinction that not a single representative picked up on. I was yelling at the screen for at least one of them to follow up on the distinction, and to nail down how much data derived from individuals that could be de-anonymized was retained after a user deletes their account. Nobody asked the question. As an aside, how utterly surreal was it to see congressional testimony with a literal stock chart being updated in semi-realtime based on the conversation that was taking place? If that is not an example of capitalism taken to an unhealthy level, I’m not sure what is.

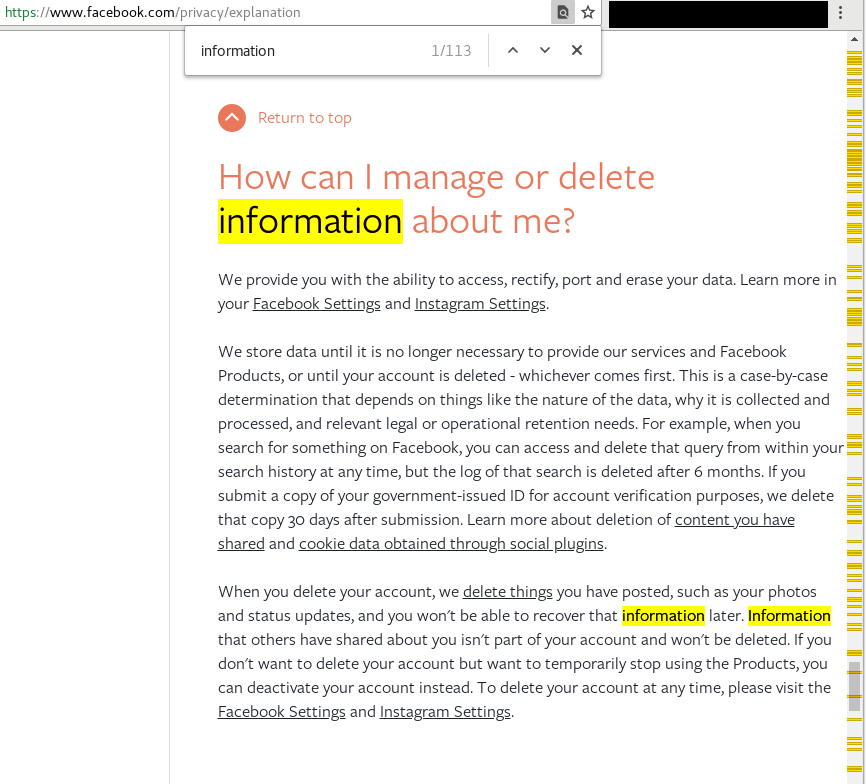

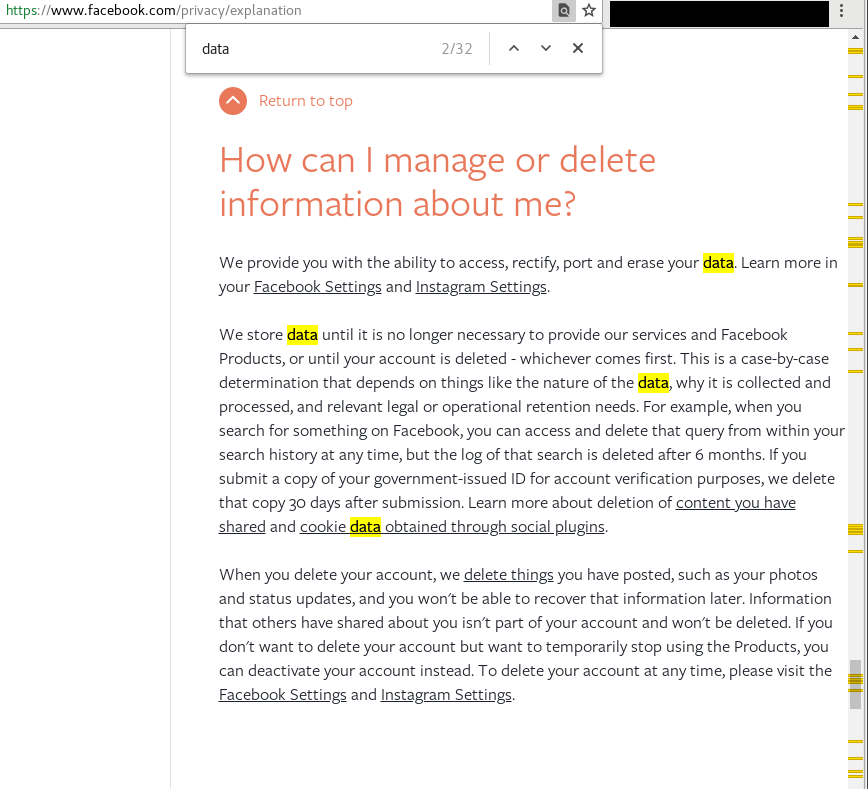

A quick, and illustrating distinction between the concepts of data and information - particularly as Facebook sees them - can be visualized by highlighting and counting each word in the Facebook privacy policy:

The yellow and orange lines along the right side show how often the word “information” shows up (a total of 113 times) in the human-readable privacy explanation document:

Note the relatively few mentions of “data” on that same page (a mere 32 times):

Now, to be fair to Facebook, they have improved the human-readable aspects of their policy and privacy documentation since their recent data spill, but I think it is telling that Facebook specifies far less of what they can (and will) do with “data” about you than the focus on “your information.” Metadata falls into the former camp, and I believe strongly that Facebook retains metadata about an individual long after that user has deleted their Facebook account. Such data is valuable, and Facebook is under no obligations to delete it based on their very careful and deliberate phrasing within the terms of use and policy documents on their website. Keep in mind that Facebook can afford the best lawyers in the world. If they want something crafted in a way that will hold up in court but be misleading as hell, they have the people to do that in spades.

Typical “I am not a lawyer” disclaimer applies here.

So with all that said, how paranoid should you be? That is a very subjective question with no single right or wrong answer. I will give it some thought for a future post.