Untrusted, levels 11 - 12

Spoiler warning:

This will contain my solutions and explanations for the various levels in the game Untrusted. If you have not played yourself, I highly recommend doing so without reading through this post. Half the fun (and learning potential) of the game is experiencing it yourself and getting the satisfaction of the “Ah ha!” moment.

</spoilerwarning>

Level 11: robot.js

This level gives us another new scenario: there is a key (k) that we need to obtain before exiting, but it is inside a chamber that the player cannot enter. Instead, a robot (R) must pick up the key, exit the chamber, and give the key to the player:

Remote control of the robot is limited to moving when the player does, or when the player chooses not to move by pressing the R key on the keyboard.

The logic on getting the robot to the key and then the player is pretty simple, especially with the pre-filled comments formally introducing us to me.CanMove() and me.move():

if (me.canMove('right')) {

me.move('right');

}

else if (me.canMove('down')) {

me.move('down');

}

Note that this solution works for the layout of this level, but if the key, exit, and/or robot were in a different position, it might not have worked. A more elegant solution would be to create a solution that could solve any layout. For example, we might come up with a solution that moves toward the key first, then the player. More to come on that.

This level begins to illustrate specific logic constructs in modular form, and how one module can depend on another; in this case the robot operating in a separate context from the player at the beginning of the level, but the player being dependent on the result from the robot.

Level 12: robotNav.js

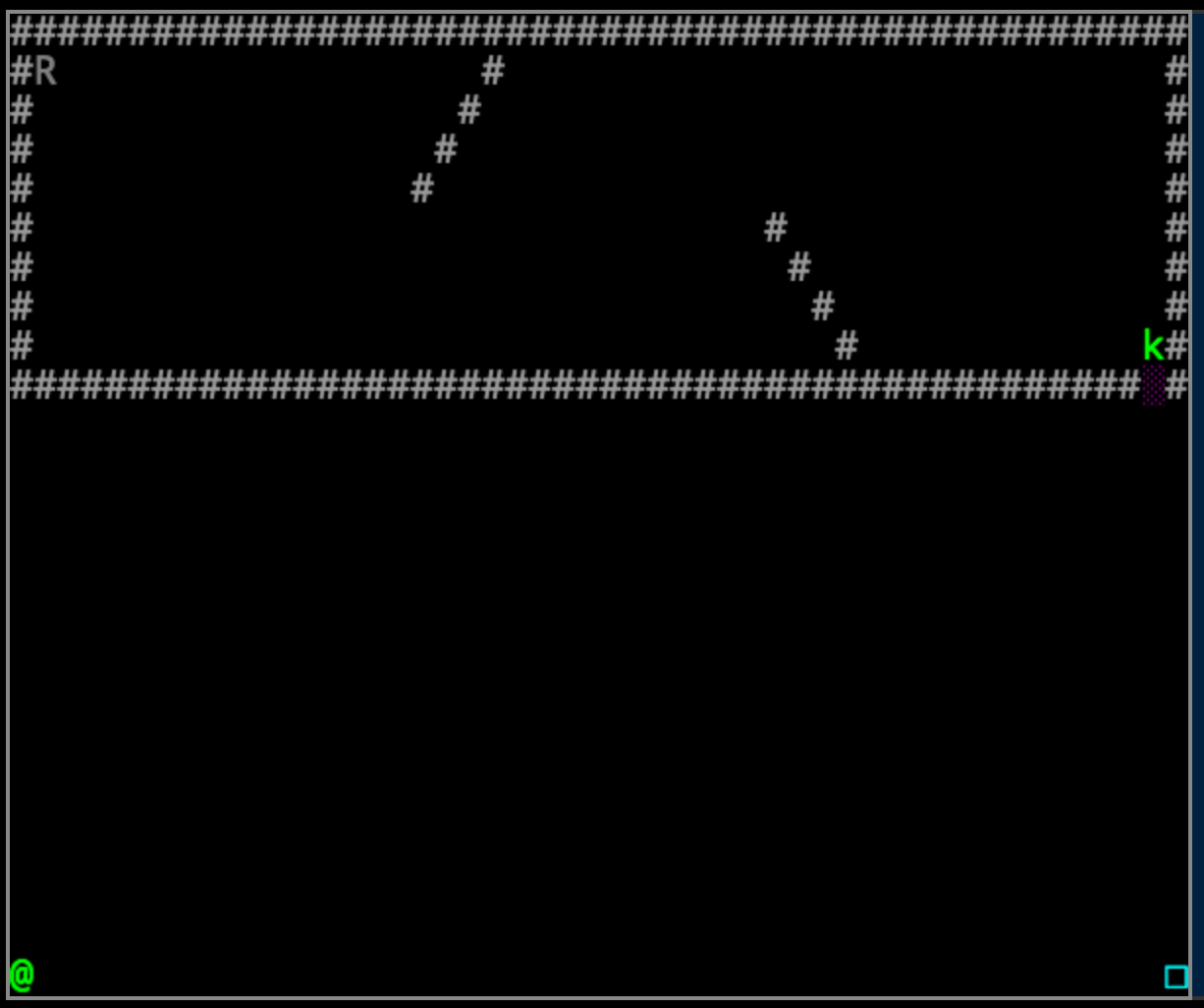

This level is very similar to the last, but with a slightly more complex layout:

We can see that our previous logic will not work for this level due to the diagonal obstructions. For a static solution to the problem, we can count the path that the robot needs to take and then program it into the robot’s logic. Once again this is not the most elegant solution, since it is layout-dependent, but it is a quick and easy solution to the problem at hand. More to come on more advanced solutions.

As I worked on solving this problem, I determined a solution pretty quickly, but encountered some issues with implementing it. My first inclination was to use loops, but due to the code that runs the game, the robot can not move more than once each time the player moves. Attempting to use a loop that activates every time the player moves results in an error message. We are violating the game’s core logic, and that is sloppy:

It also isn’t actually a solution, since the loop would reset every time the player moves.

Next I moved to implementing ‘if’ statements to program the logic. This ended up being the solution that I went with, but I ran into a quirk worth noting: We can not declare and set a new variable inside our code, since the code we are calling will execute every time the player moves. If we reset a variable, then it would reset every time the player moved. Instead, we need to make use of an existing numeric variable that we can increment without it resetting after each move. Fortunately, there is one waiting for us in the existing code:

for (var i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

map.placeObject(20 - i, i + 1, 'block');

map.placeObject(35 - i, 8 - i, 'block');

}

This code is used for placing the eight diagonal blocks that obstruct the robot’s path. The variable “i” ends at a value of “4” and we can use that for our counter without much hassle. Note that we could also have used variables “x” or “y” but they started at higher values.

With our counter identified, we can enter the following code for a static solution:

if (i < 19) {

me.move('right');

i++;

}

else if (i < 23) {

me.move('down');

i++;

}

else if (i < 38) {

me.move('right');

i++;

}

else if (i < 39) {

me.move('up');

i++

}

else if (i < 56) {

me.move('right');

i++;

}

else {

me.move('down');

}

This code simply steps the robot through a path that avoids the barriers, picks up the key, and then proceeds to move down forever. Once again, not a very elegant solution, since changing a single block in the layout, or changing the start positions could mess the whole process up.

The main concept this illustrates is that static solutions are not always best, since if we were repeatedly faced with slightly different versions of the same problem, we would have to code up a new, unique solution to each one. Far better is to come up with a universal solution that will dynamically address the problems at hand…

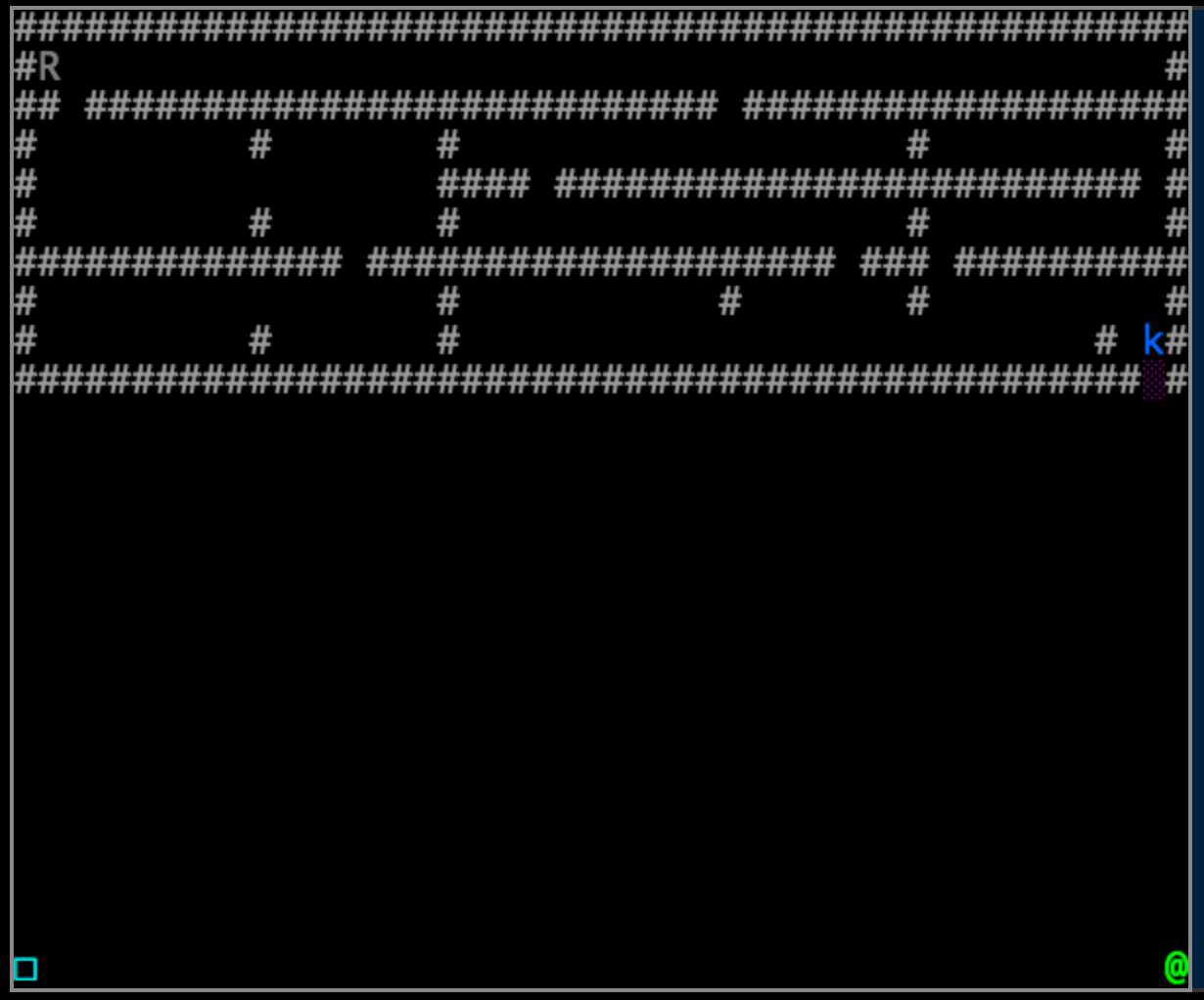

A preview of Level 13: robotMaze.js

… And here we find the example that those last two were leading up to. This time the same scenario, but the map is a complex labyrinth and it is randomly generated each time we execute our code. No more static solutions:

The hint in the level’s description mentions AI skills, so it is time for me to go to the drawing board and learn a pathing algorithm. Once I have a solution I will upload that in a new post.