Untrusted, levels 01 - 04

Spoiler warning:

This will contain my solutions and explanations for the various levels in the game Untrusted. If you have not played yourself, I highly recommend doing so without reading through this post. Half the fun (and learning potential) of the game is experiencing it yourself and getting the satisfaction of the “Ah ha!” moment.

</spoilerwarning>

Chapter 1: Breakout

Level 1: cellBlockA.js

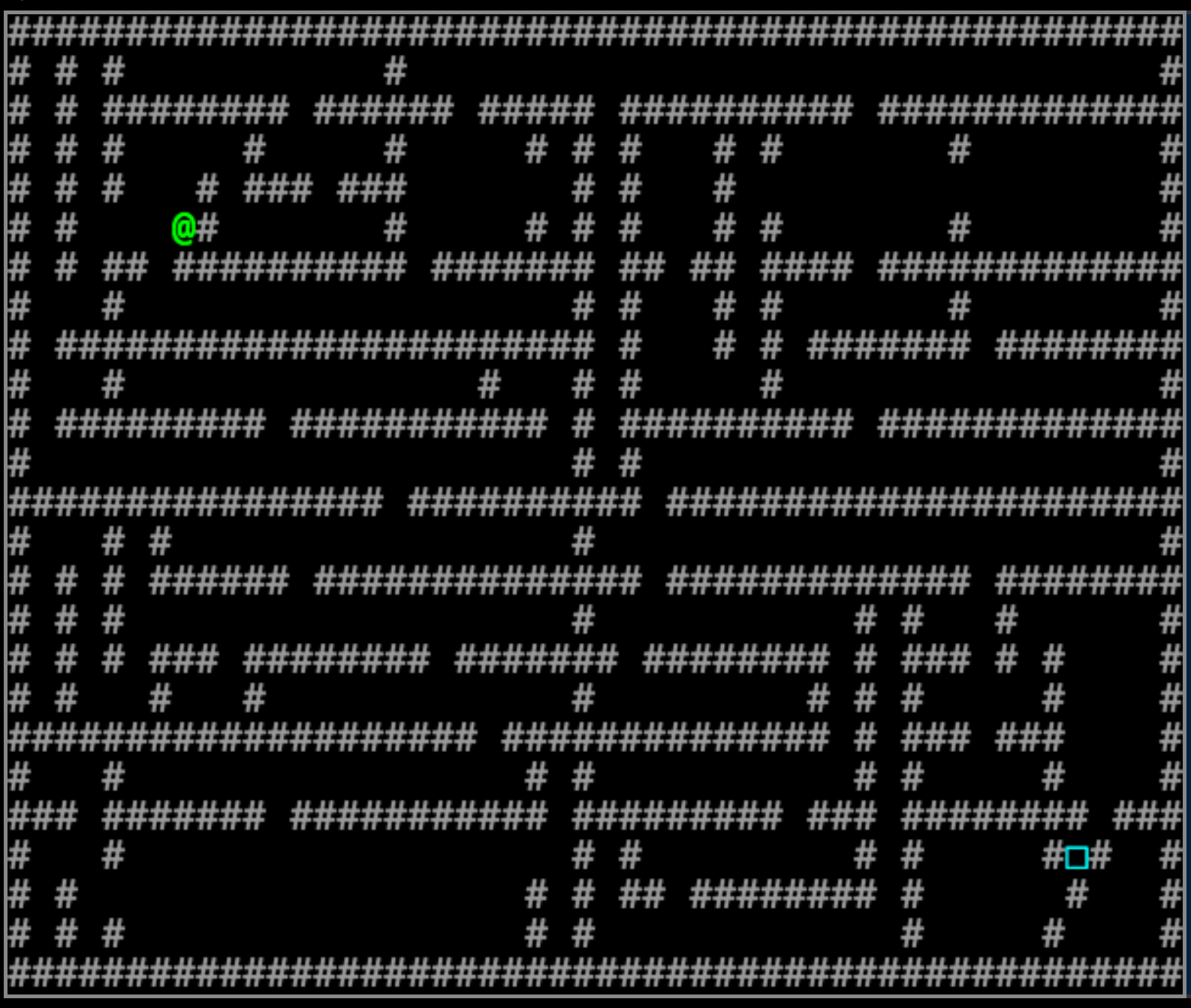

A simple introduction to the gameplay. Your ‘character’ (@) must pick up the ‘computer’ (⌘) and then move to the exit (⎕). The problem comes in the form of a cell made up of ‘blocks’ (#) surrounding the player:

Fun aside: one of the many names for the pound/hash symbol is ‘octothorpe’.

After picking up the computer, access to a representation of the game’s code is provided to the player. The editable portion of the code has to do with the placement of the ‘blocks’ around the player:

for (y = 3; y <= map.getHeight() - 10; y++) {

map.placeObject(5, y, 'block');

map.placeObject(map.getWidth() - 5, y, 'block');

}

for (x = 5; x <= map.getWidth() - 5; x++) {

map.placeObject(x, 3, 'block');

map.placeObject(x, map.getHeight() - 10, 'block');

}

This code first creates a loop that will draw vertical lines of blocks a few spaces away from the left and right canvas boundaries (5 and map.getWidth() -5, respectively), repeating from vertical position 3 to a limit of 10 spaces away from the bottom canvas boundary. Then it performs a similar process horizontally, placing blocks 3 spaces from the top boundary and 10 from the bottom, starting 5 spaces from the left boundary and ending 5 spaces from the right boundary.

It is interesting to note that because of the left/right boundaries used and the total canvas size, there is one space more on the left margin of the ‘cell’ than on the right margin. The pains of using even numbers in positioning :)

Also worth noting is that, due to the boundaries used, the two loops above actually overlap at the corners. Each block in the corners is drawn twice: first by the vertical loop, then by the horizontal one. This could make some single-digit changes to the code not make an apparent difference in the result.

To solve our adventurer’s predicament, we can modify any one of the numerical values in the code to move walls:

… or to shorten them:

Alternatively, we can simply delete the block of code that draws the walls entirely, leaving us a completely clear path:

This serves as a good introduction to the javascript constructs of loops, and variables, and it illustrates perceptible effects that changing values can have on the end result.

Level 2: theLongWayOut.js

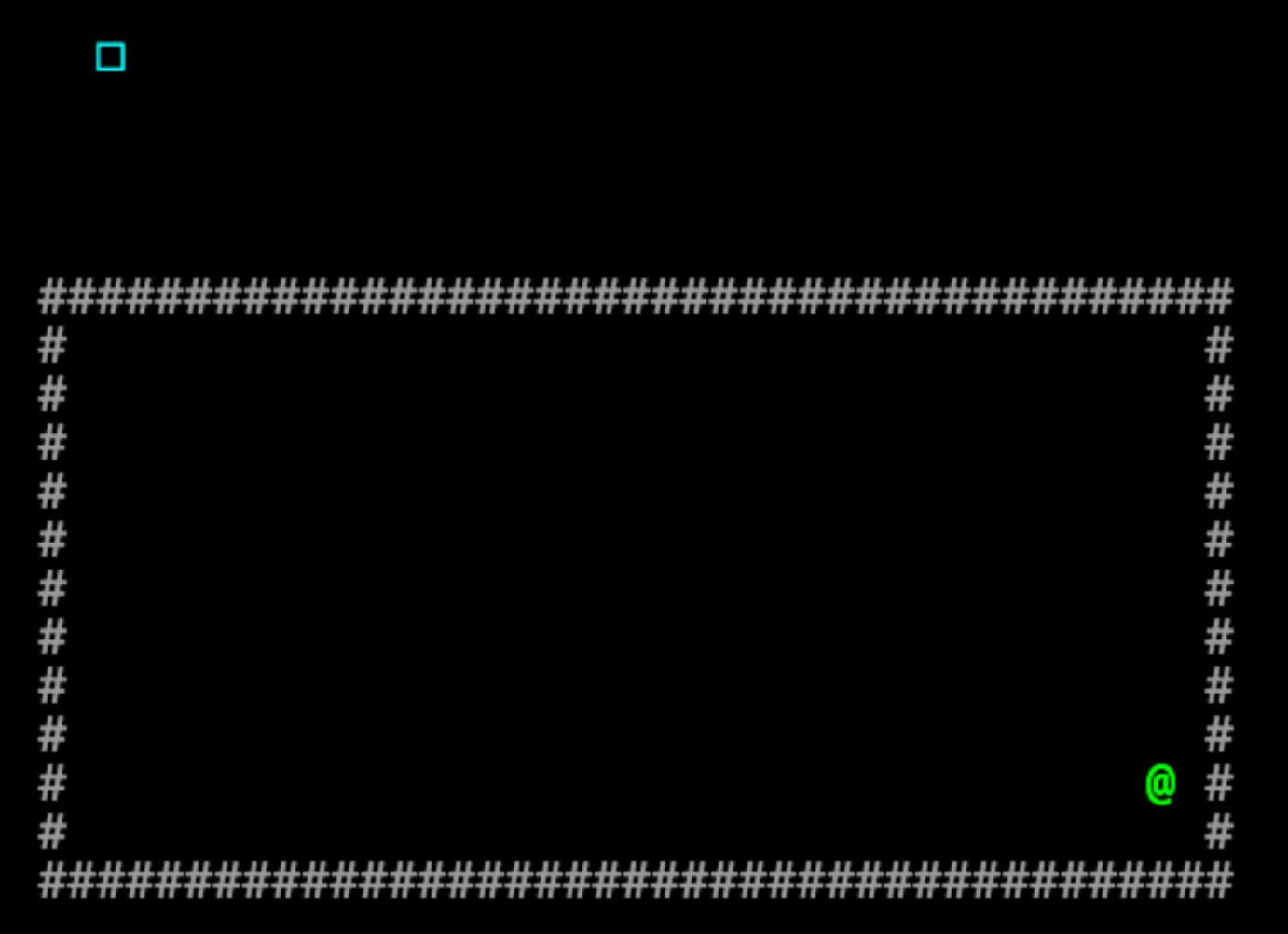

The same premise as before, only this time with a much more complicated problem to solve:

Or so it seems at first. This chapter also introduces the player to further restrictions on how code can be edited: only two lines are unprotected in the game’s code, and neither line contains any code, to begin with.

This one is simple enough, when the user is familiar with multiline comments in javascript (/* */). Beginning a multiline comment before the section of code that draws the blocks and ending it after that section will remove all the blocks in our adventurer’s way:

This illustrates the power of having multiple points of injection within functional code, and the power of applying comments to remove such code.

Level 3: validationEngaged.js

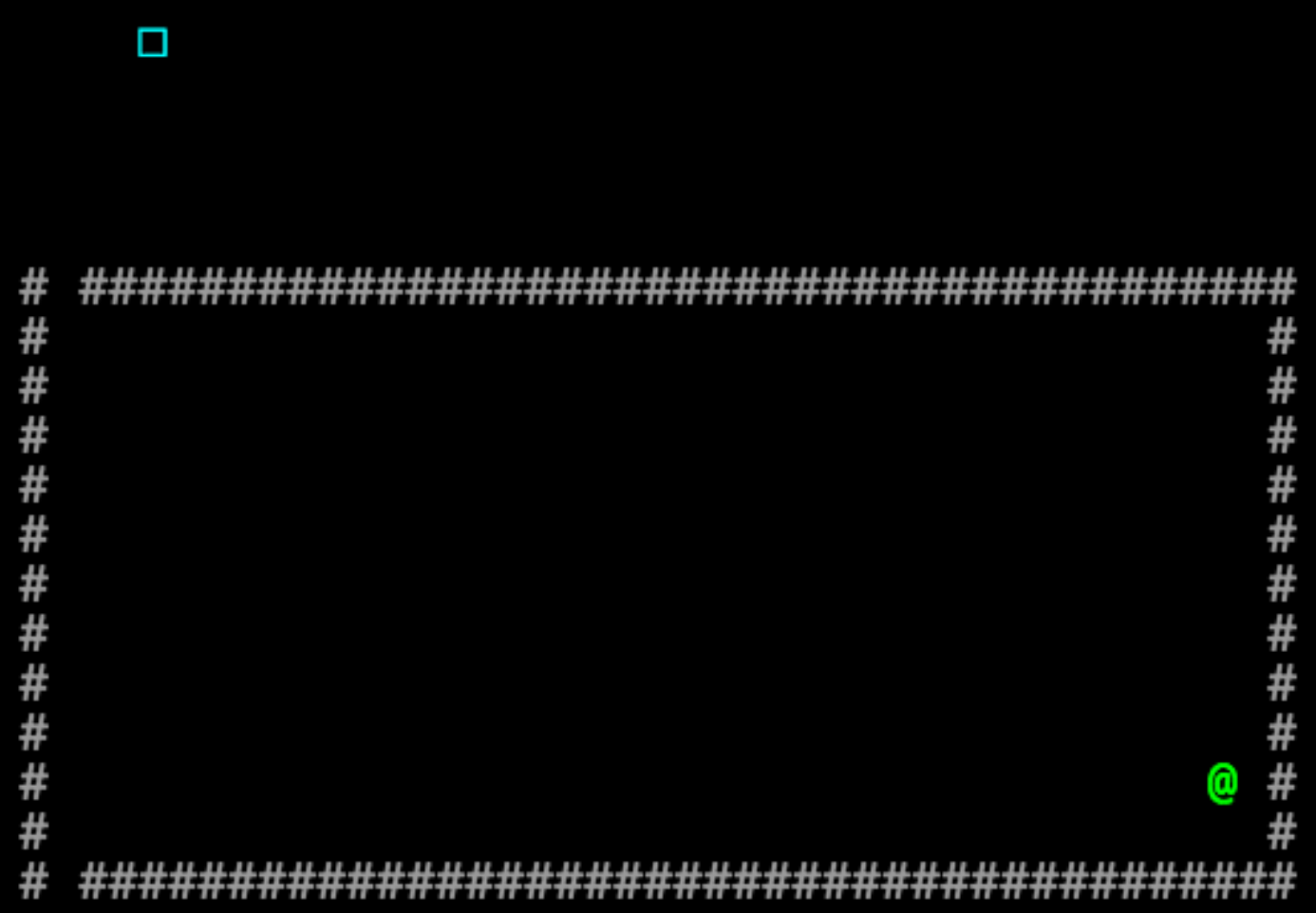

At first glance, this seems very similar to the first puzzle:

But if the player tries to repeat their prior technique of simply modifying a number or deleting code, they receive an error message:

This puzzle introduces the concept of code validation. A check has been put in place to make sure that there are enough blocks drawn. However, the check that was put in place is flawed: it only checks that the correct number of blocks is present, not that they form a cell around the player.

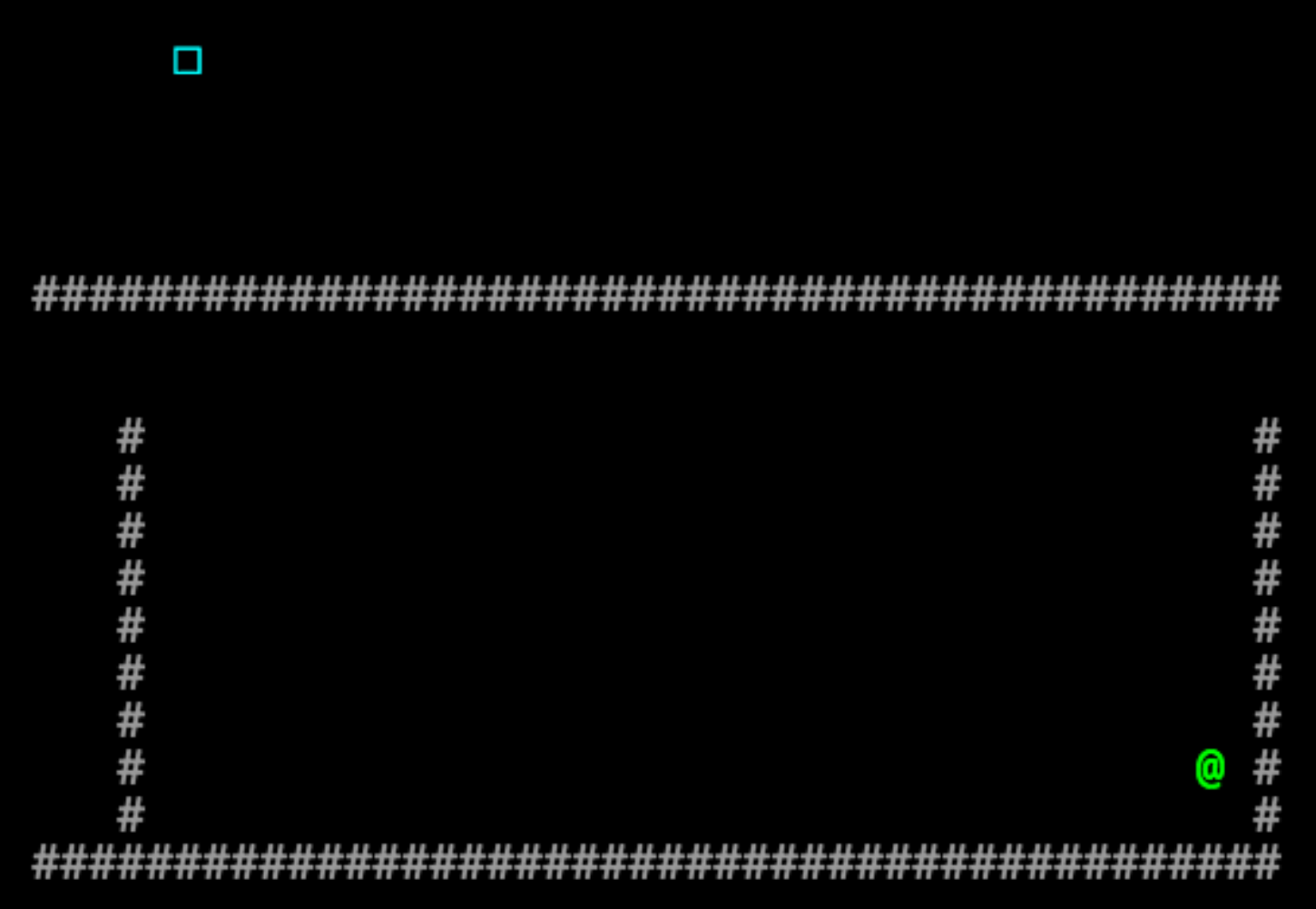

To get around this, we can either make adjustments to where the blocks are drawn (such as by moving the left wall further left, e.g. map.placeObject(3, y, 'block');):

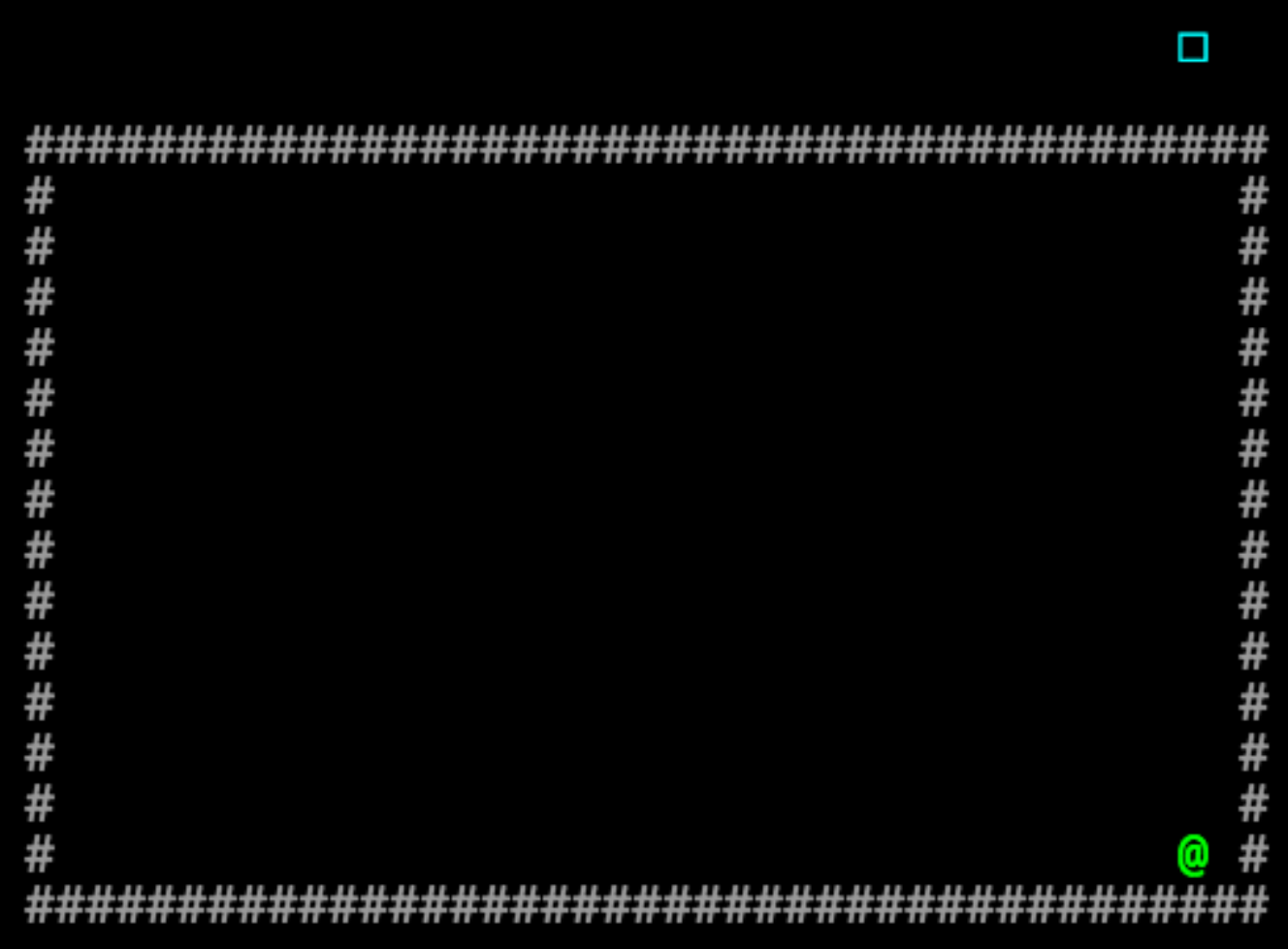

… or adjust both counts of blocks (so that we keep the same total number but position them in a way that is no longer a cell):

Code for the latter solution above:

Code for the latter solution above:

for (y = 13; y <= map.getHeight() - 3; y++) {

map.placeObject(5, y, 'block');

map.placeObject(map.getWidth() - 5, y, 'block');

}

for (x = 2; x <= map.getWidth() - 5; x++) {

map.placeObject(x, 10, 'block');

map.placeObject(x, map.getHeight() - 3, 'block');

}

Both of these solutions suffice because the validation check passes; there are still 104 total blocks in each, but they no longer prevent the player from reaching the goal. This is a good simplified example of how a flawed validation check in an application can allow for tampering of values that the designer did not foresee.

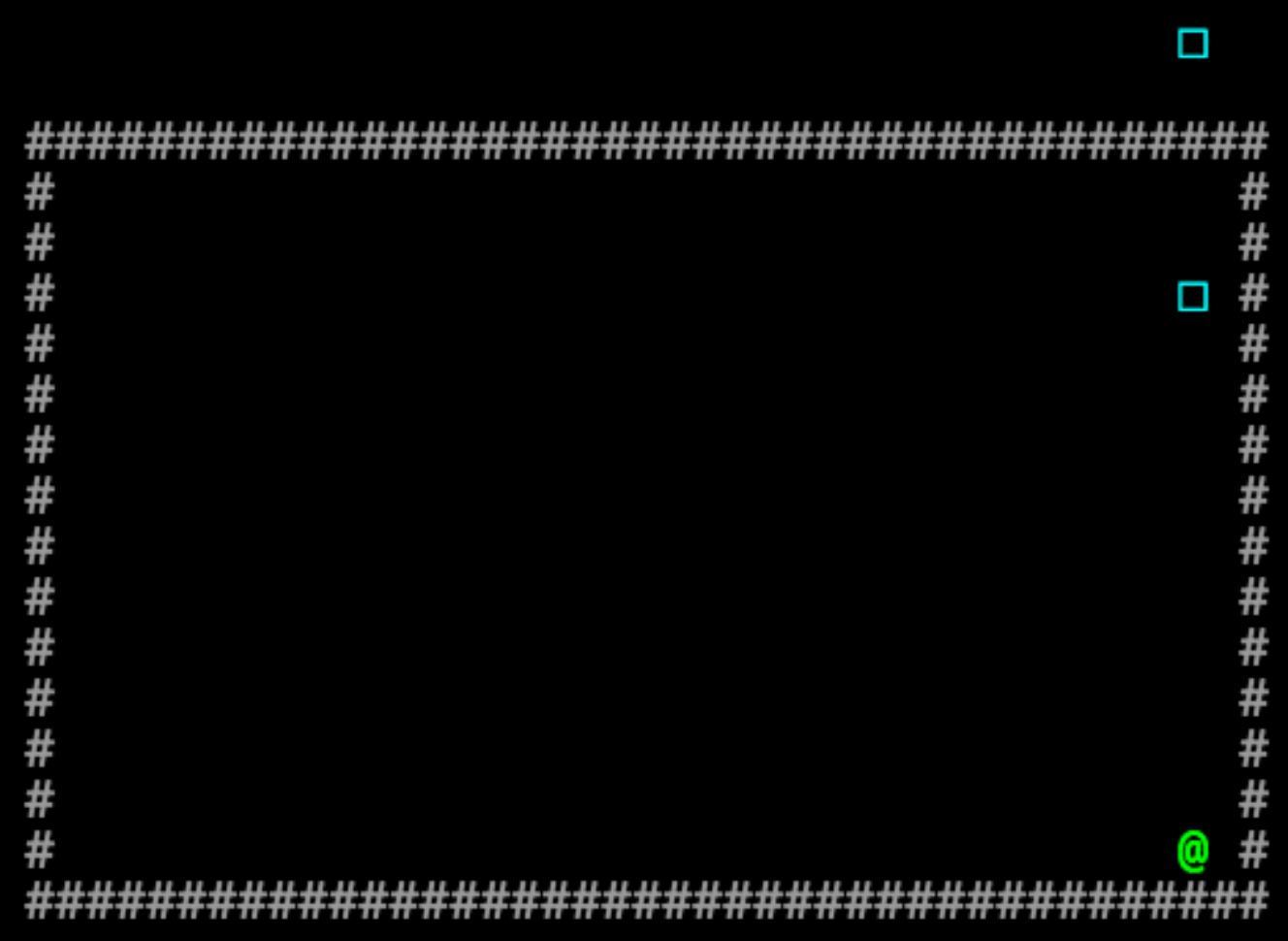

Level 4: multiplicity.js

Another day, another cell. This time we are limited to a single code injection location and we can not modify existing code or comment it out since an unclosed multiline comment will fail syntax validation.

The game is helpful in pointing out that the filename of the level might contain a hint.

An attempt to re-place the player object in a better location results in an error:

… but duplicating the location of the exit is completely legal, by the game’s logic:

map.placeObject(map.getWidth() - 5, 10, 'exit');

This illustrates that while there may be restrictions in a given piece of code, those restrictions may not be enforced consistently, or there may be logical design choices that result in a vulnerability allowing arbitrary code to function in a manner that does not cause failure, but results in unexpected behavior.